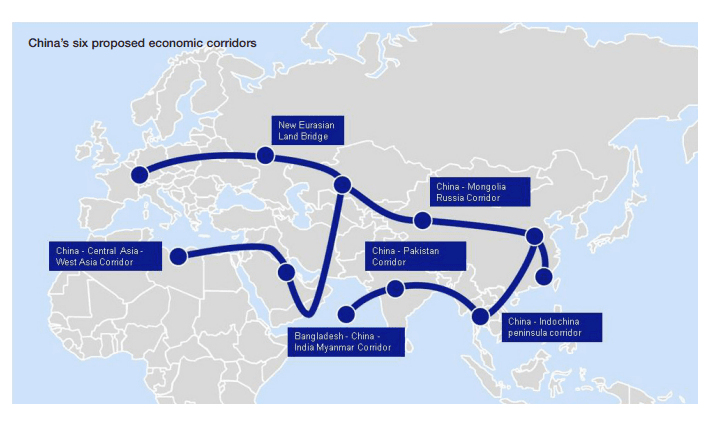

Introduction. OBOR is a combination of two outward-facing concepts introduced by Mr Xi in late 2013 to promote economic engagement and investment along two main routes. To date, reports suggest that the first route, the New Silk Road Economic Belt, will run westward overland through Central Asia and onward to Europe. The second route, the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, will probably loop south and westward by sea towards Europe, with proposed stops in South-east Asia, South Asia and Africa [1, p.7].

At the time of writing, the list of countries on the two routes had not yet been finalised. However, the geographic spread of future initiatives is expected to be ambitious. Official media have indicated that up to 60 countries may be included: preliminary maps published by the official news agency, Xinhua, show stops in countries across three continents.

Besides its political objectives, OBOR brings a strategic focus to the government’s “go out” initiative, which encourages Chinese firms to go abroad in search of new markets or investment opportunities. The OBOR push is being led from the highest levels of the government, and involvement will run across several ministries. Its initial stated emphasis will be on regional connectivity projects.

OBOR is backed by substantial financial firepower. The government has launched a US$40bn Silk Road Fund, which will directly support the OBOR mission. The fund, which became active in February 2015, is backed by the China Investment Corporation (China’s sovereign wealth fund), China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange. It will be used to improve connectivity along the “one belt, one road” by financing infrastructure, resources, industrial and financial co-operation projects, probably with an initial focus on Central and Southeast Asia. Transport infrastructure such as railways, roads, ports and airports will be a particular focus. The projects are expected to generate returns, however, and thus represent a departure from traditional aid. The chair of the fund, Jin Qi, has said that the fund will work in line with “market-oriented principles” and should generate adequate returns for its shareholders [2, p.12].

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which is being spearheaded by China and was officially established just two months previously, in October 2014, is meant to help to finance construction along OBOR as well. The bank’s stated aims are to combine China’s core competencies in building infrastructure with deep financial resources to help development in other parts of Asia.

China will provide much of the US$100bn in proposed initial capital. At its announcement, it sought participation by other Asian governments and signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with 21 of them, with assurances that it would co-operate with other funding sources such as the Asian Despite concerns expressed by the US government about the AIIB’s governance structures and lending practices, it has quickly gained momentum. By end of March 2015, more than 40 governments from five continents have applied to join the institution, including the UK, France, Australia, Brazil and Russia. Japan may sign up later, although it remains “cautious”.

China invested US$4 trillion in OBOR countries (although it has not given a timeframe for that investment) a significant proportion of which will be in infrastructure such as roads, railways and airports. However, the initiative goes much further than infrastructure and China’s central planning agency, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), has identified five priorities for the OBOR initiative in an implementation plan entitled “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road.”

These are:

- Policy coordination

China says that it will work with the other OBOR countries to develop plans for regional and cross-border co-operation and to provide policy support for large-scale infrastructure projects. So far, China has signed inter-governmental co-operation agreements with over 30 countries and international organisations and in a symbolic move, signed a letter of intent with the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific in April 2016 agreeing to promote the implementation of OBOR.

- Facilities connectivity

The OBOR initiative will focus on the transport, energy and information infrastructure that connects Asia, Europe and Africa. Projects identified include a network of highways, railways, air and sea routes, gas and oil pipelines, power grids and internet connections.

- Unimpeded Trade

China wants to reduce trade barriers, increase efficiency and promote regional economic integration. This involves working with other countries and regions to open free trade areas

and to improve customs clearance processes. To date it has signed 14 free trade agreements involving over 20 countries. The goal is to encourage two-way investments.

- Financial integration

China also wants to enhance cooperation in monetary policy, manage financial risk through regional arrangements, increase cross-border cooperation between credit-rating institutions and systems and expand the scope of currencies settlement and exchange between countries along the Belt and Road. It is setting up a regional development financial institution, called the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

- People-to-people bonds

The OBOR initiative also aims to bring people together to share information, ideas and best practices, enable cultural and academic exchanges, and promote universal technical standards.

China’s one belt one road (OBOR) initiative unveiled by President Xi Jinping in 2013, aims to restore the country’s old land and sea trade routes and to boost economic connectivity between Asia, Europe and Africa. It covers 65 countries and six economic corridors accounting for two thirds of the world’s population and one third of the world’s GDP. Here Clifford Chance experts look at the opportunities it offers and some of the challenges for investors [2, p.13].

OBOR is very ambitious and, if it is successful, will have a very deep and long lasting economic and geo-political impact. It is also intended to solve domestic issues. According to the World Bank, China has enjoyed staggering growth in the past 30 years at an average of 9 percent a year, but the Asian Development Bank says that this year growth has slowed to about 6.5 percent.

Fig. 1. China’s six proposed economic corridors

Following the global economic crisis, Chinese economic growth has been based on the government pumping money into the system, building infrastructure and creating jobs but in that process it has created excess capacity in manufacturing. That excess capacity needs to be absorbed somewhere, which is why it is focusing on the OBOR initiative.” She adds that China also wants to “transform its economy from one based on manufacturing to one based on services.

OBOR and internationalisation of the Renminbi China has been trying to globalise its currency for many years. In the Asia Pacific region, the use of Renminbi (RMB) as a trade settlement currency has now surpassed US dollars and Japanese Yen, but it is not as widely used as an investment or reserve currency. The Chinese government hopes to achieve this by using or investing RMB in projects in OBOR countries to encourage widespread acceptance of the currency. In 2014, the Chinese state-owned Silk Road Fund was established to finance OBOR projects. It is capitalised to about £25 billion and has four major investors:

- the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), which owns a vast amount of Chinese foreign currency reserves;

- CIC – the Chinese Sovereign Fund;

- two Chinese policy banks, the Export-Import Bank of China and China Development Bank.

China is also setting up a regional development bank – the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). The UK was the first country to China’s six proposed economic corridors sign articles of agreement with the AIIB and around 50 other countries are in the process of signing up. AIIB was initially capitalised at £65 billion of which China contributed around £20 billion.

There is a lot of money being committed by the Chinese government and the Chinese public and private sectors into helping the countries along the OBOR to develop infrastructure and other projects. For example, President Xi Jinping has pledged US$46 billion to boost Pakistan’s infrastructure and China has invested in rail and power projects in Indonesia [3, p.11].

The scale of the infrastructure projects has really stepped up.” China’s Silk Road Fund is investing in Yamal LNG, a US$27 billion natural gas project in the Russian Arctic. “It is an equity investor. It is the off-taker. It is supplying the kit. It is supplying the loans. It’s an indication of the type of deals that Chinese companies and banks are doing in cooperation with international sponsors and with international banks.

On projects such as this, RMB is increasingly viewed as a trade or financing currency. “If your supplies come in from China, your offtakes are for China and your loans come in from China, then Renminbi is the natural currency to use for financing that project. Multiple billion loans will be made in Renminbi and used in a completely pari passu way across the capital structure.

China is going through a steep learning curve in all aspects of financing OBOR. Let’s take for example, export credit insurance. China’s own version, Sinosure, is not as developed as UK Export Finance, France’s Coface or Japan’s JBIC. It is a single bank product worked with by institutions gathered together in a syndicate.

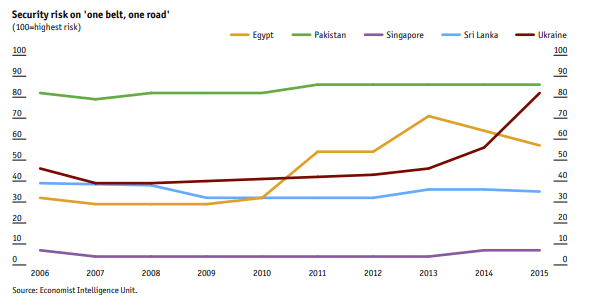

The Chinese institutions are grappling with the challenges of the scale of the projects and the size of finance required, but also with a lot of things that are new to them such as hedging, There are a number of challenges facing OBOR including the risk of political instability in the countries it will pass through. Infrastructure projects such as railways, highways and power stations depend on continuing and constant government support. However, many countries in the OBOR region are subject to frequent political upheaval which can have an impact on policy, and the implementation and success of projects. For example, the Sri Lankan government, which was appointed early last year, suspended work on a US $1.4 billion port project, which had been agreed by the previous administration, citing various irregularities including a lack of proper permits and approvals. The project was on hold for a year but has now started again. The Chinese developer estimates that the shutdown cost it more than US $380,000 a day. These examples send a clear warning message to the Chinese investors that they should not lose sight of the implications of political risks. Although it can’t be fully eliminated, it is something to be aware of and prepared for.

Other challenges relate to the different regulatory and legal systems in the countries along OBOR. Many of these countries are still developing so their legal and regulatory systems may not be so sophisticated, may be incomplete and may not have been tested for foreign investments. For example, a US$1.1 billion Chinese high speed rail project in Indonesia was also suspended just days after work began, due to incomplete paperwork, it was alleged. As a result, the Chinese consortium received a permit to build only 5km of the proposed 150 km rail line. The project is now back on track but it has sparked controversy in Indonesia as politicians have argued that it is too expensive and not suited to local needs.

Chinese institutions are grappling with the challenges of the scale of the projects and the size of the finance required.

In addition, most Chinese banks are comparatively less experienced in crossborder and international transactions, or transactions on a very large scale and are still very focused on domestic lending. They may not be fully aware of typical project finance models or the multi-national risks involved. It is crucial that before any investment decision is made and before contracts are negotiated, that you identify the risks and work out how to address them.

The Chinese experience of project finance is quite different from that in the West. China has laws that restrict guarantees that can be given by state entities so the concept of Public-Private Partnerships just doesn’t work in China. You cannot guarantee debt in the same way from a state organisation. China takes a more commercial rather than government liability perspective, shifting the risk much more to the private sector [4].

Security law in China focuses around physical assets such as land, buildings and machinery but in large projects a lot of value is in the contracts, the cash sitting in an account and how you control the arrangements. Many of the Chinese bankers on these deals are learning how to structure security arrangements over those sorts of assets for the first time.

OBOR will provide opportunities for the UK. While many of the deals being done are transacted out of Hong Kong due to its location, much of the expertise for doing deals in Africa is based in London. The money will not necessarily be purely Chinese money, it will be a collaboration between different institutions likely done under English law, so there’s a reason for these deals to come to London. And China also thinks of London as a place that gets things done so I think there will be opportunities in delivering OBOR projects.

It is crucial that before any investment decision is made and before contracts are negotiated, that you identify the risks and work out how to address them.

Fig. 2. Security’s risk on “One belt, one road”

The strong policy support behind OBOR may prove a weakness if Chinese actors, be they government planners, SOEs or private companies, fall into a false sense of security that government support will guarantee their success. Preliminary provincial government plans for OBOR all indicate that a very strong investment push is already under way to support the initiative through building up domestic infrastructure. The business strategies of many of these provinces’ local champions are incorporating OBOR into their near-term plans to absorb output that will not be used domestically. Local banks are promising financial banking, as are provincial governments.

Sichuan’s plans for OBOR provide an illustrating example of the level of provincial ambitions. It is encouraging its industrial enterprises to transfer surplus production capacity abroad, anticipating that this will, in turn, facilitate the export of equipment, raw materials and products from Sichuan.

It is especially promoting contracts in electricity, construction and oil pipeline construction, with another list of products that can target these markets including around 140 categories. The president of Dongfang Electric Corporation, a state-owned manufacturer of power generators headquartered in Sichuan, has hailed OBOR for presenting a rare opportunity for Sichuan equipment to be sold abroad.

Its efforts are supported by local authorities. The provincial government has committed to raising the “supporting level of credit” to help participating enterprises. It will offer training for local enterprises to apply for national funds. A three-year action plan will soon be issued, and it will probably include trade and bilateral investment targets.

Conclusion. The OBOR holds rich promise for Chinese companies looking to expand overseas. But if companies stumble in the markets into which they have expanded, there will ramifications for both them and the financial institutions that have backed these efforts. Failing to assess risks appropriately may mean that the domestic preparations were wasted. OBOR is China’s grand plan, but careful planning will be needed for it to succeed.

.png&w=640&q=75)