Introduction

Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) companies thrive or falter based on how effectively they manage their product portfolios across multiple categories. Portfolio architecture – the strategic design of a company’s mix of product lines and stock-keeping units (SKUs) – plays a pivotal role in brand growth. Striking the right balance between maintaining core offerings, nurturing hero products, and introducing innovation SKUs is especially critical in competitive FMCG markets. This is evident in high-growth regions like the Middle East and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), where rising incomes and local consumer nuances demand savvy portfolio strategies [1]. Leading local players (e.g. in the Middle East, Saudi-based Almarai in dairy, bakery, and poultry) have built robust multi-category portfolios by leveraging intimate knowledge of regional tastes. At the same time, global FMCG firms in these regions face the challenge of serving diverse consumer needs while avoiding unmanageable complexity. This article examines how a well-crafted portfolio architecture – with careful trade-offs between SKU breadth and depth – can fuel sustainable brand growth. We discuss the roles of core, hero, and innovation SKUs in the portfolio, the depth-vs.-breadth decision and relevant frameworks (BCG Matrix, Ansoff Matrix, etc.) to guide strategic choices. Real-world examples from the bakery, poultry, and dairy sectors (supplemented by other FMCG categories) will illustrate best practices and common pitfalls. Ultimately, balancing continuity and innovation within the product mix is key to winning both at the shelf and on the bottom line.

Portfolio Architecture and Its Impact on FMCG Growth

In essence, portfolio architecture refers to how a company structures its range of products – spanning multiple categories and SKUs – to maximize market coverage and growth synergies. A thoughtful portfolio strategy can boost market penetration, operational efficiency, and brand equity, whereas a haphazard one can dilute resources and confuse consumers. FMCG history shows that more is not always better: adding endless flavors, pack sizes, and variants can create complexity that undermines growth [6]. For example, Bain & Company reported that between 2000 and 2011 the total number of SKUs in Spain’s consumer goods market grew 40%, yet sales per SKU in stores declined, as proliferation led to lower productivity per item [6]. Unchecked variety not only raises supply chain and production costs, but also clutters retail shelves, causing low-rotating SKUs to cannibalize shelf space from top-sellers. Thus, an overly broad portfolio can attack growth and profits in subtle ways [6]. On the other hand, an overly narrow assortment risks missing consumer segments or ceding niche opportunities to competitors. The goal is optimal assortment: enough breadth to cover key categories and consumer needs but enough focus (depth in key SKUs) to achieve efficiency and impact.

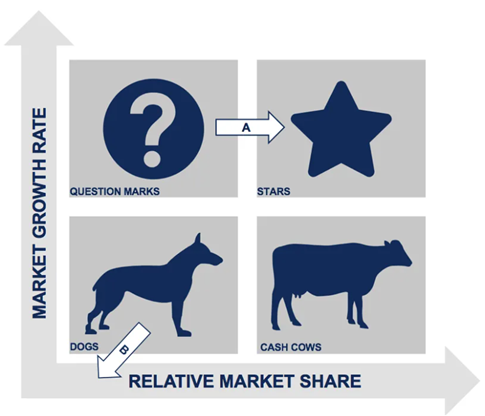

To guide these decisions, executives often turn to classic strategic frameworks. The BCG Growth-Share Matrix, for instance, is a time-tested tool for portfolio analysis. It classifies a firm’s products or business units into four categories – Stars, Cash Cows, Question Marks, and Dogs – based on market growth rate and relative market share figure 1 [2]. High-share, high-growth items (“Stars”) typically warrant heavy investment, whereas low-share, low-growth items (“Dogs”) may be candidates for divestment or discontinuation. The BCG Matrix helps managers prioritize resources among core brands and new ventures.

Fig. 1. BCG Matrix is a business planning tool used to evaluate the strategic position of a firm’s brand portfolio

Complementing this, the Ansoff Matrix (Product/Market Expansion Grid) provides a lens for growth strategy – whether through market penetration (existing products in existing markets), product development (new products to current markets), market development (entering new markets with current products), or diversification (new products in new markets) figure 2 [3]. Each quadrant carries different risk: penetrating more deeply with core SKUs is the least risky, while diversifying into entirely new categories is most radical. Together, such frameworks encourage viewing the product portfolio as a dynamic mix of investments: nurturing cash-generators, cultivating rising stars, and selectively experimenting with innovations.

Fig. 2. Ansoff Matrix is used to evaluate the relative attractiveness of growth strategies that leverage both existing products and markets vs. new ones, as well as the level of risk associated with each

Crucially, portfolio architecture is not a one-time decision but an ongoing strategic discipline. Leading companies establish formal processes for portfolio review and innovation management. For example, Godrej Consumer Products – an emerging-markets FMCG firm active in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East – formalized a stage-gate innovation pipeline across categories, while simultaneously focusing on “revitalizing our core products to maintain a strong product portfolio” [7]. This ensures that new product development (e.g. flavor extensions, format innovations) is rigorously managed and aligned with overall brand strategy, rather than draining resources from core brands. Top executives also recognize that balancing core vs. new is key to resilience. In the Middle East, a region now ranked second globally in commitment to innovation (with 58% of companies qualifying as “committed innovators” vs 45% globally) [14], successful FMCGs marry global innovation best practices with local market insights. In sum, portfolio architecture links marketing strategy (which products for which consumers) with innovation strategy (how to sustain growth long-term), under the constraints of operational feasibility.

SKU Breadth vs. Depth: Trade-offs in Portfolio Scope

A fundamental decision in portfolio design is how broad versus deep the product assortment should be. Product line breadth refers to the number of different product lines or categories a company offers, whereas product line depth refers to the number of variations within each line (e.g. flavors, sizes, formats) [13]. In other words, breadth is about covering a wide range of consumer needs across categories, while depth is about offering choice and specialization within a particular category. Both strategies have benefits and drawbacks:

- High Breadth (Wide Portfolio): Offering a broad array of product types can help an FMCG firm diversify revenue streams and appeal to a broader customer base. For instance, a company like Almarai in the Middle East expanded from its core dairy business into bakery, fruit juice, poultry, and even infant nutrition, leveraging its brand to become a one-stop food and beverage provider. This breadth has driven consistent revenue growth across core Gulf markets, with bakery and poultry expansions complementing the mature dairy category [10]. A broad portfolio can also strengthen a firm’s position with retailers by occupying multiple shelf sections and enabling cross-category promotions. However, pursuing many categories can stretch a company’s capabilities. Managing disparate businesses requires distinct supply chains, R&D, and marketing approaches. Broad portfolios risk becoming sprawling and unfocused if not curated carefully.

- High Depth (Deep Portfolio in Fewer Areas): Alternatively, a company can focus on a narrower set of categories but offer great depth of choice within each – becoming a category specialist. This strategy can cater to diverse consumer preferences in that niche and build a reputation for authority in the category. For example, a bakery snacks brand might offer dozens of variations of croissants, cakes, and biscuits to cover every flavor and occasion. Specialty retailers often favor depth over breadth, aiming to dominate a particular category with extensive options [12]. The trade-off is that too much depth can overwhelm consumers and complicate operations. Studies indicate that past a certain point, incremental SKUs add minimal new sales but exponentially more complexity [6]. As one supply chain expert quipped, companies keep adding SKUs “willy-nilly” without ensuring each variant truly earns its keep [8]. Each SKU introduced incurs costs – in production changeovers, inventory, shelf slotting, etc. – so a proliferation of variants can erode margins and agility. The key question is always: does this new SKU add sufficient consumer value and incremental revenue to justify its existence? If not, it may simply cannibalize sales of core SKUs or confuse shoppers.

Many FMCG firms, in fact, have discovered the hard way that an over-extended product lineup can hurt performance. Nestlé SA, the world’s largest food company, launched a major SKU rationalization program in 2022 to prune low-performing products and refocus on impactful ones [11]. In early 2023, Nestlé’s CFO noted that deliberate cuts of “low-growth and low-margin products” had a short-term drag on sales volumes, contributing to a –0.5% real internal growth in Q1 2023, but was expected to yield net positive benefits by year-end. These benefits included improved service levels and more resources freed for high-rotation items. Similarly, Coca-Cola undertook a “ruthless” SKU reduction during the 2020 pandemic, extending even to discontinuing entire brands, in order to prioritize fewer, stronger offerings [4]. According to Coca-Cola’s CEO James Quincey, the company “ruthlessly prioritized core brands and SKUs to strengthen the resilience of [the] supply chain”, and later decided to streamline its brand portfolio by exiting “zombie” brands that were not worth continued investment. This move, while painful (net revenue fell in the short term amid the SKU cuts), was aimed at improving operational focus and margin in subsequent quarters [4]. These cases underscore a paradigm shift in FMCG: bigger portfolios are not always better – smart simplification can drive efficiency and growth.

That said, finding the right level of breadth and depth requires nuanced analysis. Retail dynamics play a role: some retailers still prefer to “compete on variety,” believing that a wider assortment creates a perception of choice for consumers [5]. As one analyst noted, a supermarket cannot stock only the #1 national brand and a private label – shoppers expect to see the #2 and #3 brands as well to feel they have a real choice. If a manufacturer cuts too deep, it might lose placements to a competitor’s SKU. A cautionary tale is Wal-Mart’s experience in the late 2000s: after aggressively rationalizing its product assortment to trim “unproductive” SKUs, Wal-Mart discovered customers still wanted many of those items, forcing the retailer to reinstate around 8500 items it had delisted [15]. Moreover, certain slow-moving SKUs have indirect value (e.g. a gravy mix that doesn’t sell huge volume but drives sales of roast chicken, a companion product). Such complementary effects mean one cannot rely purely on item-by-item sales data; basket analysis is needed to see the full picture [5].

In practice, leading FMCG companies adopt a balanced approach: continuous pruning and cultivation. They routinely analyze SKU performance, often finding that a small minority of SKUs drive the bulk of revenue (the 80/20 rule) and that a “long tail” of fragmented SKUs contributes little. These firms implement ongoing portfolio reviews to eliminate the true underperformers (the “dead wood”), while carefully managing regional or retailer-specific SKUs and limited-time offerings. As one industry expert advises, “when an SKU is clearly not paying its way then delist! Get rid of the dead wood and put your scarce resources behind what is successful on the shelf” [8]. He recommends a structured, board-level process to review SKU productivity, rather than ad-hoc or politically driven decisions. Not every low seller should be cut – some serve niche segments or strategic roles – but every SKU should have a purpose. The end result of such discipline is a leaner, stronger portfolio. Bain & Company, after working with various FMCGs, observed that trimming the bottom-tier SKUs (often cutting 10–20% of total SKU count) can yield a double benefit: increased sales for the remaining core SKUs and significant cost reductions [6]. In one case, a company that cut nearly half of its tail SKUs (reducing total SKUs by 10%) saw 16% gains in revenue per SKU and a 45% drop in complexity costs. Another category saw sales grow 17% despite a 42% reduction in SKUs, as consumers shifted to the streamlined assortment. These examples show that judicious reduction of depth (where it is unproductive) can actually enhance overall performance – a case of “selling less to sell more” [6].

At the same time, companies must be ready to expand breadth or add depth when it truly meets a market need or fuels growth. For instance, Almarai’s push into new categories like seafood and frozen bakery products in 2023 reflects a strategic broadening of its portfolio to tap unmet demand [10]. The company explicitly stated that “product portfolio expansion and continual focus on operational efficiency will assist to overcome challenges” such as market saturation in core businesses. Likewise in the CIS region, Russia’s agribusiness giant Miratorg evolved from a meat producer into a multi-segment food company by adding new product lines (frozen vegetables, ready meals, etc.) to its portfolio [9]. Miratorg leveraged its vertical integration and quality reputation in meats to offer a wider range of frozen foods, thereby increasing its share of consumers’ wallets while maintaining its core brand promise. These moves illustrate that adding breadth can unlock new revenue streams if a firm has the capabilities to deliver quality in those new segments. The decision to broaden or deepen the SKU mix thus hinges on strategic fit and operational readiness: Will a new SKU or category drive incremental growth? Does it align with brand positioning? Can the supply chain handle it efficiently? A rigorous, framework-based analysis – using tools like BCG (to consider market share/growth prospects) and Ansoff (to consider new markets/products risk) – helps answer these questions before making portfolio moves.

Defining Core, Hero, and Innovation SKUs

In optimizing portfolio architecture, FMCG managers often categorize their SKUs into different roles: core, hero, and innovation SKUs. Understanding these roles is essential to allocate resources and make trade-offs:

- Core SKUs: These are the essential, base products that form the backbone of the business. Core SKUs typically are the high-volume, reliable sellers that meet sustained, mainstream consumer demand – often equivalent to a company’s “bread-and-butter” products or cash cows. They may not always be glamorous, but they deliver consistent revenue and profit, and represent the brand’s fundamental promise. For example, a dairy company’s core SKUs might include plain white milk, basic cheese, and natural yogurt – staple products that have steady demand. Core SKUs usually enjoy wide distribution and are prioritized for shelf space and supply continuity. Strategically, core SKUs warrant defensive investment to maintain their market share (since they are often in mature segments). They are also the benchmarks of brand quality in consumers’ eyes. For instance, if Almarai’s core fresh milk or a bakery’s standard white bread disappoints consumers, the brand’s overall reputation would suffer. Thus, companies treat core products with great care: ensuring consistent quality, competitive pricing, and marketing support to keep them relevant. In portfolio terms, many core SKUs are analogous to Cash Cows in the BCG matrix (high market share, low growth markets) – they generate cash that can fund other initiatives [2]. A key strategic task is to keep core SKUs “fresh” and defend their position even as markets evolve. This may involve occasional “renovation” (minor improvements or packaging refreshes) to address changing consumer preferences without altering the fundamental proposition [7]. Godrej’s focus on “revitalizing our core products” to maintain a strong portfolio is one example of how core SKU stewardship is an ongoing effort. In summary, core SKUs are the stable foundation of the portfolio – they require continuous nurturing and protection.

- Hero SKUs: A relatively small subset of the portfolio can be classified as hero products – the flagship offerings that drive disproportionate brand growth, visibility, and shopper preference. Hero SKUs are often those that every shopper knows and looks for, and which contribute a large share of sales and profits for both the manufacturer and retailers [16]. They tend to be the stars of the lineup (some may literally be BCG “Stars” with high share and growth). Importantly, hero SKUs are not defined only by internal sales metrics; they are strategically significant products that resonate strongly with consumers and are pivotal for the category [6]. Bain & Company describes hero SKUs as the “critical” items with the highest potential to win with shoppers and retailers – not just by size, but by how meaningful they are to consumers’ needs and to the retailer’s assortment. These are the items that “help the category grow” and whose success builds on itself: high volume leads to economies of scale, yielding better margins that can be reinvested in further growth initiatives [6]. A hero SKU could be a market-leading product (e.g., the number-one brand of spreadable cheese in a region) or a signature product synonymous with the brand (e.g., a cookie brand’s most famous flavor).

Hero SKUs warrant concentrated attention. Research has shown that focusing on a few hero SKUs can boost overall performance more than spreading efforts thin across many minor SKUs. Retailers appreciate hero SKUs because they are reliable traffic drivers with fast rotation [6]. In fact, companies that identify and double down on their hero products can often convince retailers to give those items more shelf space while trimming low-rotation SKUs – a win-win for both parties. An illustrative example is the strategy of “power brands” or “power SKUs” employed by some FMCG firms. Mondelez International, for instance, in recent years prioritized a set of its power brands (like Cadbury, Oreo, etc.) for investment and innovation, focusing on those heroes to drive global growth [17]. Similarly, Bain’s analysis of leading consumer goods players found that many are overcoming the fear of SKU reduction by demonstrating that a few hero SKUs, if fully supported and continuously renewed, can serve shoppers better than a long tail of undifferentiated variants . A concrete case: A meat producer, after trimming its portfolio to focus on core winners, actually saw faster growth – it cut ~10% of SKUs (mostly tail) and achieved 16% higher revenue-per-SKU and huge cost savings, effectively “turbocharging growth” by focusing on heroes [6]. Hero SKUs often enjoy the majority of marketing spend as well, as companies seek to maximize their impact. They are the products highlighted in consumer communications, in-store displays, and innovation efforts (more on that below). In summary, hero SKUs are the growth engines and brand exemplars – the company should do everything to ensure they remain strong (availability, promotion, quality) and keep delighting consumers.

- Innovation SKUs: These are the new products and novel variants introduced to the market to address emerging consumer needs, test new ideas, or spur growth in stagnating categories. Innovation SKUs can take many forms – a line extension (new flavor, new format, limited edition), a genuinely new product concept in an existing category, or a foray into a completely new category. They correspond to product development or diversification strategies in Ansoff’s framework. By nature, innovation SKUs carry higher uncertainty: they may become the next hero product or they may fail to gain traction. FMCG companies invest heavily in innovation – the largest players spend billions on R&D and product launches annually [16] – yet the success rates are sobering. Studies in mature markets have found that only ~15% of new FMCG products survive beyond their second year. Many new SKUs fail to meaningfully add volume to their category, and some end up cannibalizing the company’s own sales. Indeed, there is a well-documented risk that excessive innovation can hurt overall growth by diverting resources away from supporting the existing winners (core/hero products). Bain researchers describe a pattern where managers, seeing growth slowdown in their top products, unleash a “host of new products” to compensate – resulting in a flood of variants that consume advertising, shelf space, and management attention, ultimately “causing more bleeding to the core portfolio”. In other words, a frenetic pace of innovation without focus can undermine the very brands that made the company successful.

Given these risks, smart companies approach innovation SKUs as a portfolio in itself – managing the mix of incremental vs. breakthrough innovation and ensuring new launches complement (rather than cannibalize) core offerings. One useful concept is the 70-20-10 rule of innovation: allocate ~70% of innovation resources to enhancing or sustaining core products, 20% to adjacent opportunities, and 10% to truly transformational ideas. Studies have found that companies following this kind of balanced innovation portfolio significantly outperform those that over-invest in radical innovation at the expense of core, or vice versa. Essentially, core and hero products should not be neglected; many innovations should aim to “reboot” or refresh the heroes rather than constantly chase the next big thing [16]. A classic example is Heinz ketchup: instead of launching unrelated new sauces, Heinz introduced an upside-down squeezable bottle for its core ketchup – an innovation on a century-old product that still yielded a 6% sales boost (when the rest of the category grew only 2%). This shows how innovation applied to a core hero product can unlock growth by better meeting consumer needs (in this case, convenience).

Of course, some innovation SKUs do represent new frontiers – e.g., a dairy company launching a plant-based milk alternative to tap into vegan trends, or a bakery brand introducing a gluten-free range. These are important to secure the company’s future relevance. The challenge is integrating innovation SKUs into the portfolio strategy so that they are given room to grow, but also held accountable. Companies often set specific targets for new product vitality (contribution of products launched in last X years to sales) to gauge if their pipeline is healthy. At the same time, they may impose stage-gate hurdles: if an innovation SKU does not meet benchmarks (sales, trial, repeat purchase) within a period, it might be reformulated or dropped. As an industry blog advised, if new SKUs are not carefully monitored, they can “hide under the radar” and linger without justification due to internal biases (e.g., a pet project or a “regional jewel”) [8]. A disciplined approach will objectively assess whether each innovation is adding incremental value or just fragmenting the portfolio. Innovation SKUs, therefore, are the experimental and growth-seeding part of the portfolio – essential for long-term vitality, but requiring prudent management to ensure they enhance rather than detract from overall brand growth.

Balancing the Portfolio: Core, Hero, and Innovation in Harmony

The true art of portfolio architecture lies in balancing these three groups – core, hero, innovation – to achieve both short-term performance and long-term development. Each plays a distinct role, and over-indexing on any one can be detrimental:

- Protecting and leveraging core SKUs is vital for financial stability. These SKUs often fund the company’s investments in innovation and brand building. A portfolio skewed too heavily toward experimental products with weak core sales can become unprofitable or lose retailer support. Especially in markets like the Middle East and CIS where traditional staples (bread, milk, basic proteins) remain central to diets, a strong core offering builds the baseline trust with consumers. Successful firms routinely reinforce their core through marketing focused on core brand values, ensuring wide availability, and maintaining competitive pricing. For example, even as it innovates, Almarai continues to emphasize its core fresh dairy’s quality and freshness – core products that made it a household name. A healthy core provides the “cash cow” base (in BCG terms) that can be re-invested into growth areas. However, companies must guard against core complacency. Consumer preferences evolve, and core SKUs need occasional updating (e.g., reduced sugar formulations, fortified variants) to stay relevant. In dynamic markets, brands that cling to an aging core without innovation risk decline. Thus, the mantra is to “renovate the core while innovating for the future.”

- Elevating hero SKUs to their full potential is another key priority. It is not enough to merely identify one’s hero products; companies must also allocate outsized support to them. This can mean concentrating advertising on those SKUs, ensuring they are in stock and visible at retail, and expanding their reach. Hero SKUs often can travel across markets – a product that is a hit in one country might be introduced to another (with localization) to replicate success. For instance, a dairy firm’s hero Greek yogurt in one region could be launched in another market riding on its success formula. Cross-pollinating hero products is a growth lever. Furthermore, heroes should be the focus of much innovation as discussed: rather than launching brand-new brands, improving or extending a hero product can yield better ROI. Bain analysts term this using innovation to “keep heroes fit” and even turn them into “superheroes”. This involves continuous upgrades or extensions that enhance the hero SKU’s appeal – such as new pack sizes to target new consumption occasions, new flavors that complement the core flavor, or product improvements (e.g. a recipe tweak to make a product healthier). By doing so, the hero product stays fresh and maintains consumer interest over years. A caution is that brand teams shouldn’t declare every SKU a hero; hero status must be earned by market impact. A slim portfolio where “everything is a priority” actually means nothing truly is. Instead, choices must be made – often a handful of SKUs (the 5–10 that drive the majority of sales) are designated as heroes, and receive strategic priority. Companies that have done this, like those in Bain’s study, have seen faster growth and improved retailer relationships by simplifying the conversation to a few powerhouse SKUs [6]. Retail buyers, inundated with thousands of product options, appreciate when a manufacturer brings a clear focus on what will grow the category. Thus, focusing on heroes is a way to align with both consumer demand and retailer interests.

- Fostering innovation SKUs wisely completes the triad. Innovation is the engine of future growth and adaptation. However, it must be guided by strategy. Leading firms create innovation portfolios that align with overall brand positioning and category growth opportunities. A useful framework is to categorize innovation projects into core innovations (improvements to existing products), adjacent innovations (extensions into related categories or segments), and transformational innovations (new-to-company or new-to-world products). As noted, a proportional investment (like 70-20-10) ensures that most effort goes into low-risk, near-term payoff projects (which often involve core or hero SKUs), while still allocating resources to explore new frontiers. For example, an FMCG firm in the bakery sector might spend the bulk of its product development on improving its core bread recipes and packaging (core innovation), a smaller portion on developing, say, gluten-free or premium artisan lines (adjacent innovation), and a bit on researching something truly novel like 3D-printed nutrition bars (transformational). By doing so, the company secures today’s business and plants seeds for tomorrow. Moreover, integration of innovation SKUs into the core business is crucial once they prove themselves. A common pitfall is treating new products as side experiments; if an innovation SKU starts gaining traction, it should be scaled up and potentially moved into the core portfolio (and perhaps become a hero). An example is Dannon Oikos Greek yogurt in the U.S.: Danone launched it as a new SKU to ride the Greek yogurt trend (an innovation at the time), and when it took off, they aggressively scaled it, making Oikos a core brand that now rivals their traditional yogurt lines [16]. In contrast, innovation that doesn’t meet expectations should be either improved rapidly or pruned to contain costs. Successful companies iterate on new SKUs quickly – using test markets, consumer feedback, and agile development – to refine the proposition or decide to fail fast. The stage-gate process mentioned earlier at Godrej is emblematic: it’s a structured approach to evaluate innovation projects at checkpoints, ensuring only the promising ones move forward [7]. Finally, innovation should align with brand strategy: every new SKU should answer why this company/brand is best suited to offer it. That clarity helps in marketing the product and in determining whether it fits the portfolio or if it’s an outlier that could confuse brand identity.

When core, hero, and innovation SKUs are balanced and aligned, the result is a resilient and dynamic portfolio. The core business fuels profitability and trust, hero products drive growth and brand leadership, and innovation feeds the pipeline of future core and hero products. Managing this balance is an ongoing process. Market conditions, consumer trends, and competitive actions all require periodic rebalancing. For instance, during economic downturns or supply chain crises (like the COVID-19 pandemic), many FMCG firms refocused on core SKUs – simplifying assortments to ensure supply and meet basic demand [4]. Coca-Cola’s prioritization of core brands during the pandemic is a case in point. Conversely, in times of booming demand or shifts (e.g. a sudden craze for high-protein snacks), companies might lean more on innovation SKUs to capture the wave. The portfolio strategy should be agile, with decision mechanisms to scale up winners (whether core, hero, or new) and scale down laggards. Cross-functional coordination is also important: portfolio decisions should involve marketing (for consumer insight), sales (for retailer perspective), supply chain (for feasibility), and finance (for profitability analysis). This ensures that when, say, a long-tail SKU is cut, everyone agrees on the rationale (e.g. it frees capacity to make hero SKUs with fewer stock-outs).

In practice, a well-balanced portfolio might look like this: Core SKUs making up perhaps 50–70% of revenue – stable and efficient; a few Hero SKUs within that core contributing a large chunk of growth and receiving majority of investments; and a stream of Innovation SKUs contributing, say, 10–20% of revenue and aimed at driving future expansion. These proportions can vary, but importantly, each category reinforces the others. The heroes bring consumers into the franchise, the core keeps them loyal and satisfied day-to-day, and the innovations excite them and preempt competitor disruption. A tangible example can be drawn from the dairy industry in an emerging market: the company’s core plain yogurts and white milk (core) deliver scale and trust, its new fruit yogurt line becomes wildly popular (turns into a hero product), and concurrently it experiments with plant-based milks and lactose-free variants (innovation) to address new health trends – some of which may become future heroes. By managing resources across these, the brand grows in both volume and relevance.

Conclusion

In the FMCG sector, strategic portfolio architecture is a decisive factor in achieving sustainable brand growth. Companies that thoughtfully balance SKU depth and breadth – offering consumers variety where it matters, but not so much as to breed inefficiency – tend to outperform those that either spread themselves too thin or cling to a stagnant assortment. The interplay of core, hero, and innovation SKUs is central to this strategy. Core products provide continuity, revenue stability, and brand heritage; hero products act as focal points for differentiation and category leadership; and innovation products drive renewal and address emerging opportunities. The Middle East and CIS markets exemplify these dynamics: local champions with broad yet focused portfolios are holding their own against global competitors, leveraging core strengths while innovating for local tastes. For marketing professionals and brand managers, the take-home message is clear – portfolio decisions should be made as strategically as investments in new markets or factories. Tools like the BCG Matrix and Ansoff Matrix remain valuable for mapping where each product stands and where growth should come from next. Moreover, a culture of continuous portfolio optimization (cutting underperformers, bolstering winners, and boldly investing in promising innovations) is crucial. As one industry saying goes, “You can’t be everything to everyone” – and effective portfolio management is about choosing where to play and how to win.

In closing, a winning FMCG portfolio is coherent (each SKU has a role and supports the brand’s promise), competitive (meeting consumer needs better than rivals’ offerings), and cost-effective (optimized for profitability and operational simplicity). Achieving this is an ongoing journey. It requires marrying data-driven analysis (sales, margins, market trends) with strategic foresight and sometimes tough calls to simplify. The reward, however, is significant: companies that master their portfolio architecture are positioned to both maximize current market performance and adapt to future trends, ensuring enduring brand growth in the fast-moving consumer goods arena.

.png&w=384&q=75)

.png&w=640&q=75)