Introduction

Each time an actor steps onto a stage or stands before a camera, they enter into a tacit dialogue with an entire epoch of theatrical techniques – from the ancient mask to the Stanislavski method. But today, a new participant is welcome to the process, an interlocutor, another machine intelligence who will be able to analyze scripts, understand facial expressions, and create a digital double with an appearance that will hardly distinguish from the real one. To many people, it may just seem like an ordinary technological upgrade; what we are actually going through is a transformation of cultural paradigms: the playhouse for artistic illusion has extended itself through statistical modeling), and luck-and-chance that was previously the sole prerogative of human imagination are now dispersed among the weights of a neural network such that every probability gets built into the character.

The pace of these changes surprises even an industry accustomed to technological avant-gardes. Business at large is not lagging: in a recent McKinsey study, almost half of respondents reported having already experienced concrete consequences of AI adoption firsthand, and the share of such companies grew by three percentage points in just one year (Singla et al., 2025). This statistic is not mere context; it clarifies why the conversation about acting and algorithms is happening here and now: at any other tempo, it would simply be impossible to keep up with the transformation of stage craft into a field of computable probabilities.

But the entertainment sphere advances toward transformation less straightforwardly. Deloitte analysts calculated that in 2025, the largest film studios are allocating less than three percent of their production budgets to generative tools, cautiously limiting themselves to auxiliary tasks – from localization to contract management (Arkenberg et al., 2024). Such moderate financing paradoxically coincides with sensational headlines about digital doubles, producing a sense of disjunction between hype and pragmatics. Thus, the topic’s relevance reveals itself in the very collision: the industry simultaneously aspires to radical automation and fears losing the unique human voice that has hitherto been the backbone of dramatic art.

And then, there shall be social tension accompanying this technological breakthrough. Many fear that with the massive introduction of artificial intelligence, there will be much work left for them to do. It is on performers that these fears pivot: net new contractual clauses institute rights giving performers exclusive rights to use digital replicas of their likeness and voice, acknowledging that without such legal safeguards, creative freedom can lead to a loss of control over one’s own image. It is precisely the combination of rapid technological progress, studios’ economic calculus, and the growing sense of vulnerability felt by performers that turns the interaction between human and algorithm into an issue not of the future but of the present.

Materials and Methodology

The study’s materials encompass a broad spectrum of sources, including academic publications on the history of cinematographic technologies, industry reports on the dynamics of motion-capture and generative-media markets, union agreements for performers, and analytical reviews by consulting firms. The theoretical foundation comprises works describing the evolution of technical means for recording performance: from Fleischer’s rotoscope as a first step toward the mathematization of actorly movement (Fleischer Studios, n.d.) to breakthroughs in facial capture that allowed Andy Serkis’s performance to be mapped onto Gollum’s digital shell (Clarke, 2002) and reinvented the approach to recording emotions in Avatar (Guo et al., 2023). Historical retrospection made it possible to identify a regularity: each generation of tools not only expanded the technical arsenal but also shaped new aesthetic and ethical frames.

Methodologically, the research combines several approaches. First, a comparative analysis of technological trajectories is applied – from optical markers and infrared cameras to contemporary markerless systems based on inertial sensors and LiDARs. The second methodological block is a regulatory-legal and ethical-legal analysis. The SAG-AFTRA agreement with Replica Studios (SAG-AFTRA, 2024) was used to demonstrate the institutionalization of risks associated with digital voice replicas, while materials from Deloitte (Arkenberg et al., 2024) and McKinsey (Singla et al., 2025) made it possible to link studios’ financial caution with the broader acceleration of AI adoption in business. The third instrument was a content analysis of media cases and mass surveys. Wired’s reporting on generative video and de-aging algorithms in Indiana Jones (Bedingfield, 2023) and Polygon’s account of Tron’s visual ambivalence (Campbell, 2020) were compared with critics’ reactions to the digital resurrection of Peter Cushing in Rogue One (Pulver, 2017; Shoard, 2016).

Results and Discussion

It is impossible to understand why today’s actor encounters the algorithm as an equal partner without an excursion into the depths of a century, where techniques for capturing movement were born. It began in 1915, when Max Fleischer patented the rotoscope – an apparatus enabling frame-by-frame redrawing of film stock; essentially, it was the first attempt to seize the trajectory of the body and transform it into a controllable drawing and thus into a mathematical series open to analysis (Fleischer Studios, n.d.). This optics, yoking the living and the calculable, proved contagious: the 1970s saw LED markers, the 1990s infrared cameras, and by the millennium’s end, telemetry suits were reading not only skeletal mechanics but also muscular oscillations, anticipating an era of total stripping of the skin from the actor.

A threshold was crossed in 2002, when the image of Gollum led viewers to doubt where Andy Serkis’s flesh ended and the polygonal cloud began. Each scene was shot three times to overlay facial motion onto digital skin, and the actor himself demanded recognition that his performance did not vanish beneath the digits but instead condensed within them (Clarke, 2002). Thus emerged a new notion of performance capture, in which the instrument ceases to be a mere intermediary and becomes an extension of the organism; the statistical hand of the neural network enters that same secret score of which stage pedagogues once spoke.

In 2009, Avatar offered the next turn: tapes with markers yielded to head-mounted mini-cameras capturing the microstructure of the face, while server arrays interpreted muscular morphology as a set of equations into which other parameters could be substituted – from the fantastic skin of the Na’vi to a character’s altered age. James Cameron claimed that in this way it was possible to capture almost one hundred percent of the performer’s emotional spectrum, and the engineers themselves spoke of a reinvention of facial-capture methodology (Guo et al., 2023).

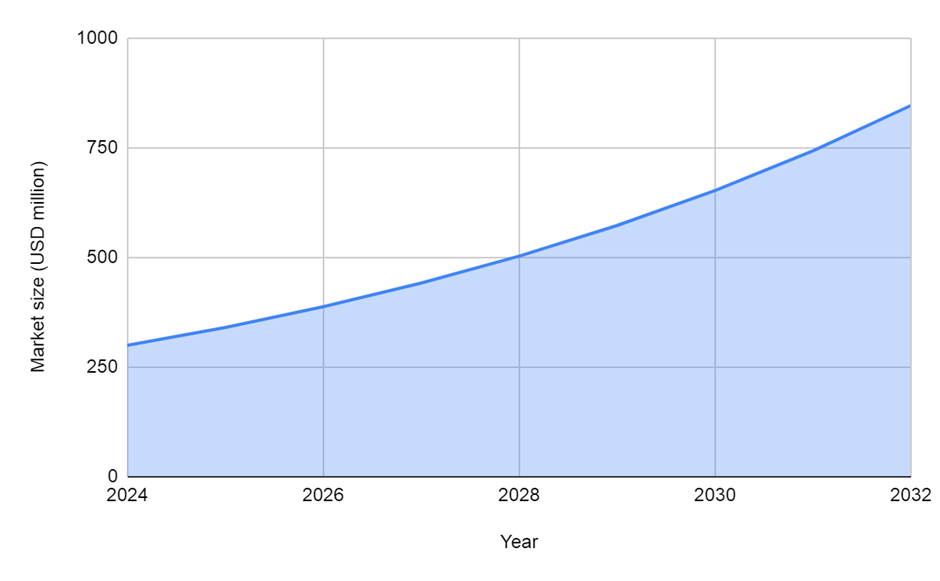

The technological pulse is reflected in financial graphs as well: according to Fortune Business Insights, the global market for three-dimensional motion capture grew from three hundred million dollars in 2024 to a projected 340.6 million in 2025 and, by their calculations, will reach 847.8 million by 2032, demonstrating an average annual growth of nearly fourteen percent, as shown in figure 1 (Fortune Business Insights, 2025).

Fig. 1. Global 3D Motion Capture Market Size (Fortune Business Insights, 2025)

The figures merely confirm it: an industry that until recently treated such systems as auxiliary now regards them as one of its core production resources.

In parallel, the phenomenon of the digital double took shape. In 2000, when Oliver Reed died unexpectedly during the filming of Gladiator, the creators employed a combination of a body double and computer graphics to complete the film, effectively reassembling the performer from digitized fragments of his face (McCormick, 2021). This moment proved pivotal: for the first time, the image of a deceased actor existed without him, like a hologram of memory, yet continued to act within the narrative.

The tempo only accelerated. In 2010, Tron: Legacy de-aged Jeff Bridges by three decades, deploying large-scale reconstruction of skin textures and muscular contractions, which provoked in viewers a mixed sensation: admiration for precision and unease before the smooth, almost waxen surface of a face stripped of the usual contingencies of age (Campbell, 2020). And in 2016, Rogue One returned Peter Cushing to the screen twenty years after his death; the VFX supervisor openly acknowledged that contesting ethical boundaries had become an inextricable part of the production process itself (Pulver, 2017).

Thus, in under twenty years, the path ran from Fleischer’s animation projector to the virtual exhumation of images, where an actorly presence became a reversible variable. There is no linear progress in this story. Each leap forward generated a new rift between technical sophistication and the feeling of authenticity, forcing creativity and law, engineering and psychology to redistribute roles anew. This very tangle of contradictions prepares the ground for the following discussion, of which algorithms today shape the corporeality and voice of the character, and whether the performer can retain within them their own breath.

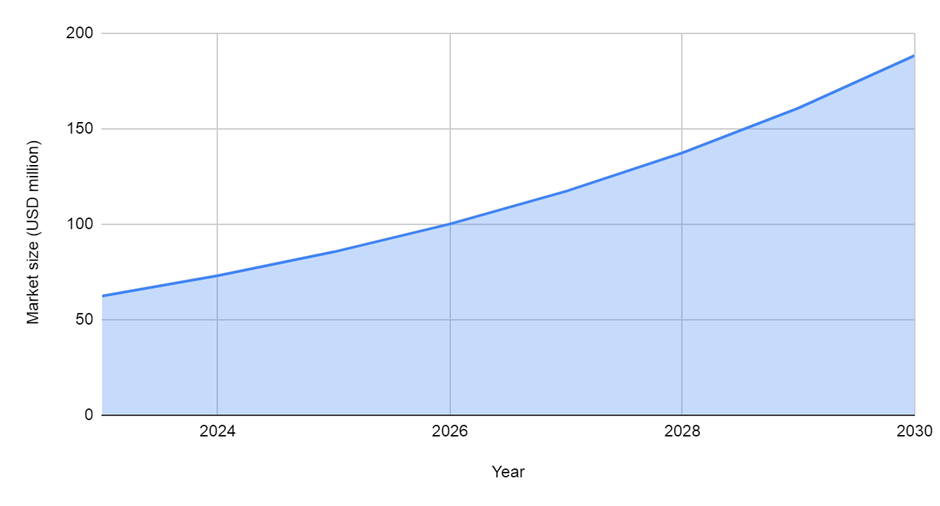

Modern facilities for capturing motion use extremely small, less than a millimeter, inertial sensors exposing skeletal and muscular motions like reading X-ray poems: it is completed with LiDAR cameras pulling the performer out of the environment into a three-dimensional network directly. At a 17.1% CAGR, this global markerless motion-capture market will grow from $62.42 mln in 2023 to ≈ $188.46 mln by 2030, as shown in figure 2 (GVR, n.d.), hence steady exponential dynamics implying substantial scaling potential for motion-capture technologies.

Fig. 2. Global Markerless Motion Capture Market Size (GVR, n.d.)

Simultaneously, cameras mounted directly on the actor’s face transmute mimetic fluctuations into a point cloud capable of instantly seizing even the tremor of an eyelash. Capturing performance no longer demands multiple takes: the director sees a rough cut right on set, and the algorithm corrects the animation like a movement coach, suggesting where to add a tremolo of the chin and how to soften the opening of the lips. Here, the actor first feels it: their physical energy bifurcates – part remains in the muscles, part goes into computational darkness – and both halves must resonate in synchrony.

At the next level, generative video appeared. Models such as Sora offer a set from text: describe a rain-soaked cobblestone street and instantly receive a one-minute fragment as if shot on a drizzly square in Bologna. Studios remain cautious, but the flow is inevitable: Wired notes that Netflix is already inserting such shots into series, and independent projects are building entire previsualizations on a generation, saving weeks of storyboarding (Schiffer, 2025). Unsurprisingly, analysts are promising nearly eight-fold growth in the generative-animation market by 2030, turning the algorithm into a hidden producer dictating the rhythm of the entire crew (Super AGI, 2025).

The next front is the voice. Timbre-generation algorithms melt phonetic individuality, allowing a non-linear model to be derived from forty seconds of recording that reproduces the performer’s breathing, pauses, and even inadvertent slips. It is no surprise that the union drew its first red line precisely here: the SAG-AFTRA agreement with Replica Studios requires separate written consent, fixes payment for each scanning session, and obliges developers to store data in encrypted form on pain of license revocation (SAG-AFTRA, 2024).

Finally, the deep retouching of time. The same suite of neural networks that removes noise from a photograph can return youth to an actor or revive a long-departed icon. In Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, an eighty-year-old Harrison Ford looks thirty-five for a quarter of an hour, and the actor himself admits: It’s my face, only pulled from the past, because the algorithm sifted through every frame of his forty-year archive (Bedingfield, 2023). But if de-aging still leans on a living presence, Rogue One went further, resurrecting Peter Cushing without his participation and eliciting a sharp reaction from critics who likened the digital resurrection to a disturbance of the peace of cinema’s cemetery (Shoard, 2016). This counterpoint – between rapture before engineering precision and fear of the loss of authenticity – sets the tone for the current dialogue between actor and algorithm.

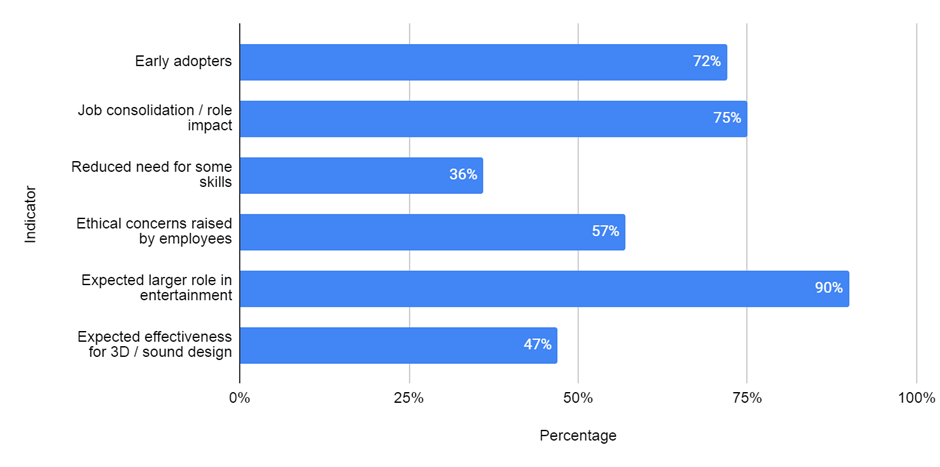

The data in Figure 3 demonstrate a combination of broad early adoption and high expectations for the expanding role of Generative AI (72% adopters, 90% expect expansion), significant impact on jobs and required skills (75% – role restructuring, 36% – declining need for specific skills), and serious ethical concerns among employees (57%). At the same time, concrete confidence in efficacy for creating 3D/audio remains moderate (CVL Economics, 2024).

Fig. 3. Survey Indicators of Generative AI Adoption and Impact (CVL Economics, 2024)

A new grammar of the profession is thus taking shape: the performer’s body is repeatedly split into coordinates, textures, acoustic spectra, and temporal layers, each of which can live an autonomous life. The actor must master the keyboard of their own flesh to conduct it together with the machine; otherwise, the digital interlocutor will gain the upper hand and turn performance into pure simulation.

The actor sits down with the script and feels that before them is no longer a static text but a pulsating topography of meanings: the algorithm, like an impassive dramaturge, highlights nodes of motivation, weighs lines, and computes the tension curve down to the last intonational comma. On the screen appears an emotional heat map: one line shimmers ruby – an alert of impending rage; another cools to turquoise – a harbinger of alienation. A word read thus cannot be spoken of in any automatic way: it forces consciousness with the many shadings that have been hidden, and the performer feels forced to search their own experience for an answer to every half-tone uncovered by the soulless yet sharp-eyed network of computation.

When it comes to reading, the partner is the very same algorithm quickly dressed up in a digital mannequin shell. This spectral interlocutor may vary the rhythm, elongate a pause, or hasten abruptly a phrase. Thus, rehearsal does not become mechanical repetition-each pass differs from the previous one as if behind the mask, alternating living partners. Because of such plasticity, the actor has to keep attention taut; otherwise, the virtual counterpart shows up the artificiality of the response. The net result is an ensemble wherein spontaneity and algorithmic plausibility meet by surprise.

Next comes previsualization: the director receives a tried-out scene in rough graphics even before the first lamp is lit on set. On the desk flicker schematic figures illuminated by virtual spotlights, yet the actor already sees where a camera angle will steal half an expression and where the lips must quiver slightly more in close-up. This knowledge is sewn into motorics in advance; by the time of principal photography, the actor’s body seeks less and asserts more, and the camera catches the performance like an arrow released along a precomputed trajectory.

Then the studio doors close, and the actor remains inside the so-called green cube. Of the familiar décor, only air and a set of markers clinging to the suit remain. Yet walls of LED panels instantly turn emptiness into a booming port, a tropical forest, or a submarine interior, and the algorithm adjusts perspective to each movement of the camera’s mind. The landscape answers to the gesture like a mirror of living mercury; the actor ceases to doubt the materiality of illusion. They step on an invisible plank, feel the creak of a non-existent board, hear the echo between bodiless panes of glass – and all this is recorded simultaneously with the performance.

The virtual studio also erases topography: a second shift can take place in another country, yet for the actor, it is the same set where yesterday stood the chamber props. A facial mask of sensors transmits expressions over fiber optics, and the character comes alive on servers that supply light, wind, and reflections in the eyes on their own. Into such a dissolved space, the performer brings the most fragile part of the craft – the intimate silence between inhalation and word – and tests whether the network can amplify rather than drown out that silence.

Thus, an odd partnership forms. The human gives heat, the machine offers back a many-sided shine, and both get what they missed. Yet the balance is thin: as soon as the code gets used to guiding, the actor may turn into just a flesh sensor sending input. The main art of now is to keep the inside drive even when the outside has been built for so long already, where each likely line of the face is worked out bits of time before it shows.

A trade used to leaning on the body sense and the art of playing swift shifts now finds itself laid out between wires and maths; those who meet the lens must learn with as much care for the masked rules of sensors as once for plastic showiness. New rites slip into the start-of-day run-through: tuning up the dead suit, making sure optical marks are clean, reading a note on how the mind net thinks about small shifts in lip top movement. Vocal warm-up has changed as well – articulatory gymnastics is joined by a spectrum run, in which the actor listens to their own voice passed through a synthetic double and learns, like a sculptor, to correct timbre so that the machine catches the diaphragm’s vibration. In place of the erstwhile fear of technology, there comes the skill of conversing with it: the performer becomes half-engineer, comprehends frame-rate parameters, understands how lighting affects tracker algorithms, and negotiates rights to the digital copy armed with legal terminology they once never considered.

Yet amid the scatter of new skills, the icy contours of risk show through. When an image can be multiplied, substituted, de-aged, or torn from context without permission, the actor’s very identity finds itself on the verge of dissolution. A specter of an invisible rival appears at castings: not a person in line, but a flawless synthetic avatar free of fatigue and fees. If a studio secures a license to a digitized performer, there is a temptation to shorten the shooting day or dispense with live presence altogether. Such labor reallocation runs up against a painful question: Will there remain room for the inadvertent slip, the stray glint in the eye, the minor glitches by virtue of which the viewer believes? In parallel, the danger of expropriation grows: one careless contract is enough for foreign algorithms to clone a face and voice in advertisements with which the performer wants no association.

But where there is a threat, opportunity also lies. Where projection makes it easier for space to be set up, performers with restricted movements equally have a chance to perform a fighting scene all inside the studio; senior masters return the old vigor of movement, and novices from far-off lands go through global casting without expensive flights. Nuances of intonation are preserved in a digital record so that what used to disappear after the final clap of the slate now becomes a continued presence: the character can exist beyond the temporal biography of the performer, developing from film to film like a musical theme whose variations will be created by future directors. No longer does age or distance or physical limitation define a boundary; no longer is geography in between the viewer and the actor, because on a planetary stage itself.

Art overturns its own bases: instead of strictly shared roles of who plays and who writes, there comes a moving plain where living urge and machine guesswork endlessly pour into one another. True mastery is now measured not only by the strength of feeling but also by the ability to steer the cold computational stream without letting it become a vortex of estrangement. If the performer accepts this game, recognizing vulnerability and resource at once, then through the wall of algorithms, there will again appear that very spark for which the viewer has for centuries listened to the stage’s breathing.

Conclusion

The conclusion is dual: on the one hand, it registers an irreversible shift – from tool to co-author – in which statistical models and neural networks have ceased to be a mere auxiliary stroke and have entered the very structure of the dramatic work, fracturing the actor’s body into a set of coordinates, textures, and temporal layers; on the other, it underscores that this technical progress does not annul but radically redefines the nature of artistic mastery, bringing to the fore the task of preserving the inner impulse as the central criterion of authentic performance. Historical retrospection from rotoscope to digital resurrectability, together with statistical confirmation of market scale, shows that we are dealing not with a fashionable wave but with a new production reality in which the algorithm can simultaneously amplify and diminish the performer’s presence.

This reality requires a revision of the professional skill set: to traditional practices of plastic expressiveness and improvisation are added competencies for working with sensors, interfaces, and the legal terms governing the use of digital replicas; the actor becomes in part an engineer and, at the same time, an advocate for their own likeness and voice. The rise of contractual limitations and collective agreements speaks to the need for institutional safeguards and the formalization of rules; otherwise, what has made technologies commercially attractive can change into modes through which individual image appropriation takes place. On the other hand, previsualization practices show that technical means are more appropriately considered as extensions rather than substitutions for creative practice, if indeed initiative stays with the human.

Risks and opportunities not only coexist, they interpenetrate: while networked doubles and synthetic avatars menace the labor market and the singularity of artistic expression, they unveil access for limited mobility actors, remote performers, as well as for the preservation of nuance in digital archives. Paradoxically, it is from this interplay that a new aesthetic task emerges – to learn to conduct a dialogue with the soulless exactitude of computation so that the algorithm does not swallow spontaneity but instead becomes an instrument for composing feeling. Upon this balance depends whether the actor remains the source of that spark for which the viewer continues to listen to the stage’s breathing.

The upshot is a pragmatic-ethical call: to preserve artistic autonomy through a combination of professional renewal, legal regulation, and critical production design. Only a conjunction of raising performers’ techno-literacy, strengthening collective guarantees, and consciously implementing technologies will turn algorithms from threat into resource – and then, as our material and discussion suggest, through the wall of computation there may again appear what constitutes the essence of the stage – the living, vulnerable, and unrepeatable impulse of the performer.

.png&w=384&q=75)

.png&w=640&q=75)