Introduction

Definition

The term spinal stenosis is used to describe abnormal narrowing of the central canal, the lateral recesses or the intervertebral foramina to the point where the neural elements are compromised. When this occurs the patient develops neurological symptoms and signs in the lower limbs [9, p. 486-487].

The conundrum of spinal stenosis, like many spinal conditions, is that putative ‘‘pathologic’’ anatomy does not equate with pain. The spinal stenosis condition implies patho-morphologic narrowing of the spinal canal, yet spinal stenosis cannot be thought of as a simple compressive lesion. What happens to the contents of the canal is more clinically relevant than what happens to the borders of the spinal canal. If compression were the sole pathologic entity in spinal stenosis, decompressive surgery would be an exquisitely efficacious procedure rendering near total, long-term relief. Empiric, longitudinal and experimental evidence suggests mechanical deformation is not the sole source of nerve root pain [1, p. 403-408; 2, p. 63-66; 3, p. 166-180].

Individuals with spinal stenosis on radiography may be asymptomatic or present with a variety of symptoms [4, p. 4-5]. When symptoms do occur, the classic presentation is leg pain upon walking, coined neurogenic intermittent claudication (NIC). NIC, a clinical diagnosis distinct from vascular claudication, occurs in patients with central or lateral lumbar stenosis who develop lower limb complaints during ambulation, spinal extension, or standing. Unlike vascular claudication, pain is typically relieved with lumbar flexion. Contrary to popular belief, not all spinal stenotic patients present with NIC. They may also present with pain at rest or frank radiculopathy with or without radicular pain. Radicular pain is sharp, band-like pain that radiates in a dermatomal distribution. Radiculopathy, on the other hand, is a neurologic condition due to nerve root injury sufficient enough to cause objective signs such as weakness, sensation loss, and reflex loss [5, p. 832]. It has become apparent that spinal stenotic patients have a multi-factorial cause of these symptoms. In the setting of patho-morphologic compression, several biochemical and biomechanical factors lead to the sine qua non of nerve root injury and the dreaded flare of symptoms [9, p. 486-487].

Causes

The causes of spinal stenosis are:

- Congenital vertebral dysplasia (e.g. in achondroplasia or hypochondroplasia).

- Chronic disc protrusion and peri-discal fibrosis or ossification.

- Displacement and hypertrophy, or osteoarthritis, of the apophyseal (facet) joints.

- Hypertrophy, folding, or ossification of the ligamentum flavum.

- Bone thickening due to Paget’s disease.

Unilateral narrowing of the inter-vertebral foramen (root canal stenosis) may result from an unresolved lateral disc herniation, post-discectomy fibrosis or unilateral facet joint ost [9, p. 486-487].

Patho-anatomy of spinal stenosis

The lumbar spinal canal houses the spinal cord / conus medullaris proximally and the cauda equina nerve roots distally. The process of aging, disc herniation, facet joint hypertrophy, ligamentum flavum thickening, disc space narrowing, and congenital stenosis which is present in individuals with achondroplasia or short pedicles can contribute to a narrowed spinal canal. This acquired or congenital morphologic narrowing appears to set the stage for, but does not necessarily induce, nerve root symptoms. Anatomically spinal stenosis can be subdivided into central stenosis and lateral stenosis [8].

Central stenosis: Central stenosis is found at the inter-vertebral level and is caused by ligamentum flavum buckling or hypertrophy, disc protrusion, hypertrophic zygapophyseal joints, and degenerative spondylolisthesis. 40% of central stenosis is secondary to soft tissue changes within the central canal [6, p. 240-246] (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Axial T1-weighted MR image demonstrating severe central stenosis secondary to disc bulge, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, and zygapophyseal joint hypertrophy [6, p. 240-246]

Lateral stenosis: Lateral spinal stenosis is a common cause of lumbar radicular pain syndromes. The lateral lumbar spinal column includes the nerve root canal (lateral recess) and the intervertebral foramen (neural foramen). These two areas together form a tubular canal through which the nerve root exits [7, p. 313-320] (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Sagittal T2-weighted MR image demonstrating multilevel central stenosis from bulging discs (white arrows) and ligamentum flavum hypertrophy (white arrows) [6, p. 240-246]

Clinical features

The patient, usually a man, aged over 50 years, complains of aching, heaviness, numbness and paraesthesia in the thighs and legs; it comes on after standing upright or walking for 5–10 minutes, and is consistently relieved by sitting, squatting or leaning against a wall to flex the spine (hence the term ‘spinal claudication’). With root canal stenosis the symptoms may be unilateral. The patient sometimes has a previous history of disc prolapse, chronic backache or spinal operation [9, p. 486-487].

Central spinal stenosis denotes involvement of the area between the facet joints, which is occupied by the dura and its contents. Stenosis in this region usually is caused by protrusion of a disc, bulging anulus, osteophyte formation, or buckled or thickened ligamentum flavum. So, symptomatic central spinal stenosis results in neurogenic claudication with generalized leg pain [10, p. 1994-2005].

Lateral to the dura is the lateral canal, which contains the nerve roots; thus, compression in this region results in radiculopathy [10, p. 1994-2005].

Patients with spinal stenosis, symptoms include back pain (95%), sciatica (91%), sensory disturbance in the legs (70%), motor weakness (33%), and urinary disturbance (12%). In patients with central spinal stenosis, symptoms usually are bilateral and involve the buttocks and posterior thighs in a non-dermatomal distribution. With lateral recess stenosis, symptoms usually are dermatomal because they are related to a specific nerve being compressed [10, p. 1994-2005].

Diagnostic imaging

Radiography

Although plain radiography cannot confirm spinal stenosis, findings such as short pedicles on the lateral view, narrowing between the pedicles on the antero-posterior view, ligament ossification, narrowing of the foramen, and hypertrophy of the posterior articular facets can be helpful hints. Flexion and extension views are useful to identify pre-existing instability before laminectomy and may be useful in determining the need for subsequent fusion [10, p. 1994-2005].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is a good noninvasive study for patients with persistent lower extremity complaints after radiographic screening evaluation. MRI should be confirmatory in patients with a consistent history of neurogenic claudication or radiculopathy [10, p. 1994-2005].

Computed Tomographic Myelography

Despite the prevalence of MRI, myelography followed by CT is still accepted and widely used for operative planning in patients with spinal stenosis; it has a diagnostic accuracy of 91%. Myelography followed by CT is best suited for patients with dynamic stenosis, post-operative leg pain, severe scoliosis or spondylolisthesis, metallic implants contra-indications to MRI, and lower extremity symptoms in the absence of findings on MRI [10, p. 1994-2005].

Other Diagnostic Studies

Electro-diagnostic studies should be used if the diagnosis of neuropathy is uncertain, especially in patients with diabetes mellitus. Needle electro-myographic study was shown to have a lower false-positive rate than MRI in asymptomatic patients [10, p. 1994-2005].

Patients & methods

This study is a retrospective analysis of 22 consecutive patients who underwent surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis at the period of April, May, June, & July 2012 at Al-Sulaimaniyah teaching hospital in Al-Sulaimaniyah governorate, Kurdistan Iraq, & in Tikrit teaching hospital in Salah Al-Deen governorate.

Inclusion criteria:

- Degenerative central spinal canal stenosis.

- Single level stenosis.

- Patients age is 55 years or older.

- Conservative treatment lasting longer than 3 months had failed.

Exclusion criteria:

- Contra-lateral recess stenosis.

- Bilateral root canal stenosis.

- Multiple level spinal stenoses.

- Inflammatory spondylopathy.

- Spinal instability.

- Spinal tumor.

Demographic data includes name, age, sex, occupation, chief complain & duration, unilateral or bilateral, clinical examination, radiological tests, response to non-surgical treatment, response to surgical treatment, & follow up.

Intra-operatively; assessment of the spine, dura, nerve roots, facet joints, & the disc state which causes the stenosis was done. The data analysis was done by using SPSS version 16.

History and Examination

When taking the patient's history, the main symptoms were spinal claudication, radicular pain, motor weakness, & back pain which were not responding to medical treatment. The duration of this history was also significant. The clinical examination was followed by a vascular investigation to exclude vascular claudication.

Radiological Evaluation

All the patients underwent MR imaging of the lumbar spine, and the extent of the spinal stenosis could be estimated. Compression of the lumbar dural sac was clearly delineated. However, we saw patients who needed further decompression postoperatively. We also routinely performed plain antero-posterior and lateral radiography of the lumbar spine prior the surgery to exclude developmental disorders.

Indications for Surgery

- Clear symptoms of neural claudication with corresponding signs of a radiological correlate.

- 3 months of conservative treatment did not improve the patient's symptoms.

- The exclusion criteria were met.

The target criterion of this study was to achieve decompression of the spinal stenosis. All patients presented with signs of neural claudication, and in all patients lumbar spinal stenosis was found on radiological examinations as the anatomical correlate. Statistical analysis of the patients regarding the distribution of age, clinical symptoms, & signs revealed that it was possible to retrospectively study the outcomes of this surgery.

Surgical Approach

Hemi-laminectomy:

The unilateral partial hemi-laminectomy was our most common choice. The spine was exposed via a midline incision. The thoraco-lumbar fascia was incised, and the para-vertebral muscles were carefully mobilized from the bony structures only on the side of the operation. Partial hemi-laminectomy of the ipsi-lateral hemi-lamina was done subsequently. The base of the spinous process was then undercut. The ligamentum flavum, which was mostly thickened, was also removed. Thereafter, the contra-lateral recess was decompressed also. This approach resulted in a good expansion of the dural sac and was used whenever possible.

Surgical Procedure:

All patients underwent surgery in the kneeling position after induction of anesthesia. Surgery was performed in a standardized manner. Care was taken in all patients to minimize facet joint resection. An undercutting technique was used to remove osteo-ligamentous structures on the opposite side. Suction drains were placed routinely. The patients were mobilized on Day 1 after surgery.

Postoperative Evaluation:

The patients were examined 3, 6, & 12 months postoperatively. The evaluation included performing a full neurological examination, determining the duration of the postoperative pain and type of pain medication, and assessing the improvement of neural claudication measured by the distance the patient could walk uninterrupted (assessment of neural claudication).

Statistical Evaluation:

For statistical analysis, the differences between preoperative and postoperative characteristics (The pain, sciatica, assessment of neural claudication, sensory & motor changes, use of pain medication, and overall patient satisfaction) were used.

Results

Patient Population: During April, May, June, & July 2012, a 22 patients with lumbar spinal stenosis met our inclusion criteria & were received all the non-operative measures regarding the management of spinal stenosis but with no benefits. All of them returned the questionnaires and were included in this study.

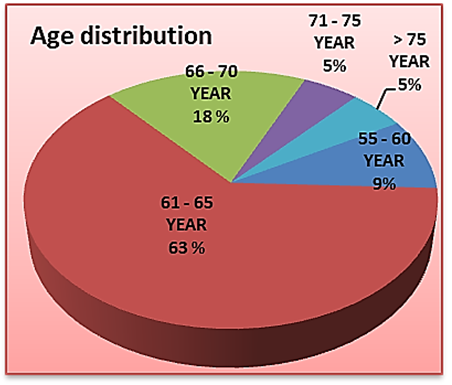

1) Age: The majority 63% of the patients who complain of spinal stenosis were between the ages of 61–65 years old (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Showing the most common age of spinal stenosis which was between 61–65 years

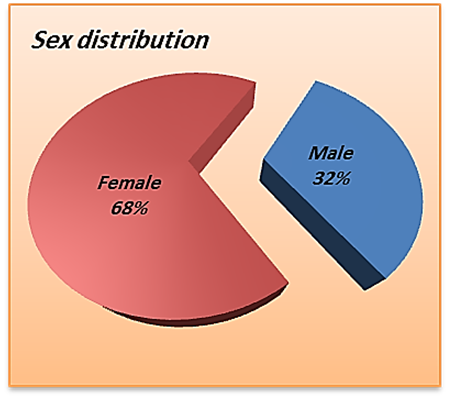

2) Sex: About the sex; the majority 68% the patients were females, while 32% were males (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Showing that spinal stenosis is more common in females than in males

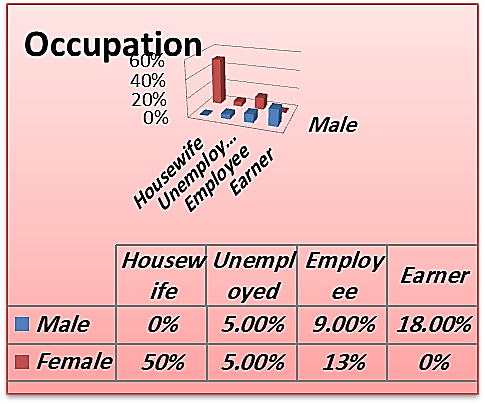

3) Occupation: Spinal stenosis was more common in housewives women (50%), while in males it was more common (18%) in earners (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Showing that the housewives women & the earner men are more affected by spinal stenosis

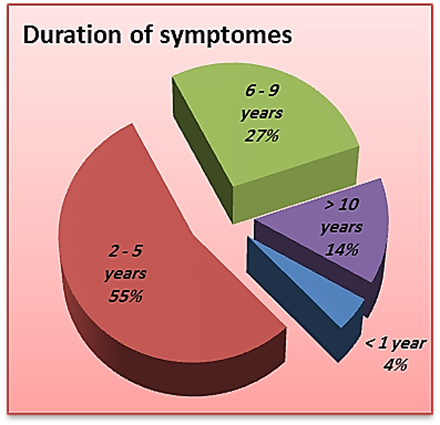

4) Duration of symptoms: The majority of patients (55%) presented with symptoms lasting between 2 and 5 years, and (4%) of the patients had symptoms lasting for less than 1 year (fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Pie chart shows the duration of symptoms of 22 patients with lumbar spinal stenosis who were operated by hemilaminectomy. The majority of patients presented 2–5 years after the onset of symptoms

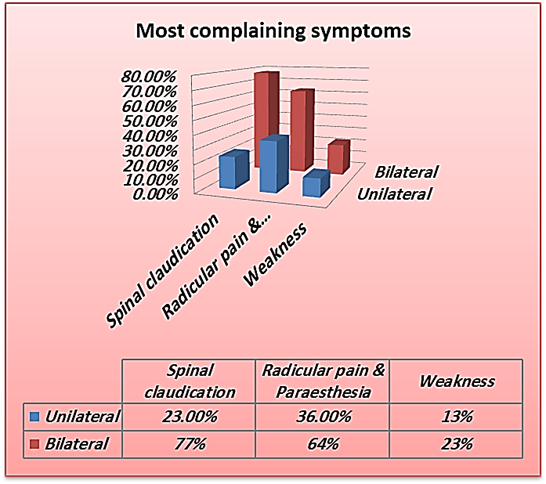

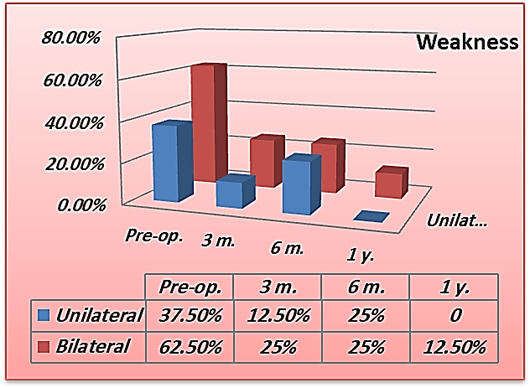

5) Most complaining symptom: All of the patients were complaining of spinal claudication, of them (77%) bilaterally & (23%) unilaterally. Radiculopathy was present in all of them also (64%), bilaterally & (36%) unilaterally, while weakness was found in about (36%) of the patients only; unilaterally & bilaterally (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Showing the most presenting symptom

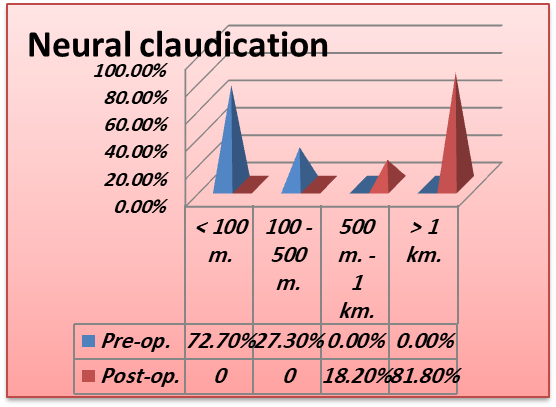

6) Neural claudication: Pre and postoperative neural claudication was assessed by the distance a patient could walk uninterrupted. There was good overall improvement after the surgery with respect to the neural claudication. Preoperatively, the majority of the patients (72.7%) could walk uninterrupted just less than 100 m., while postoperatively, more than (81%) of the patients could walk uninterrupted for more than 1 km (fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Bar chart shows the assessment of neural claudication before and after hemilaminectomy. The patients cannot walk continually and have to stop intermittently. The distance a patient can walk uninterrupted until the onset of neural claudication occurs can be measured (assessment of neural claudication). This distance was greatly improved after hemilaminectomy

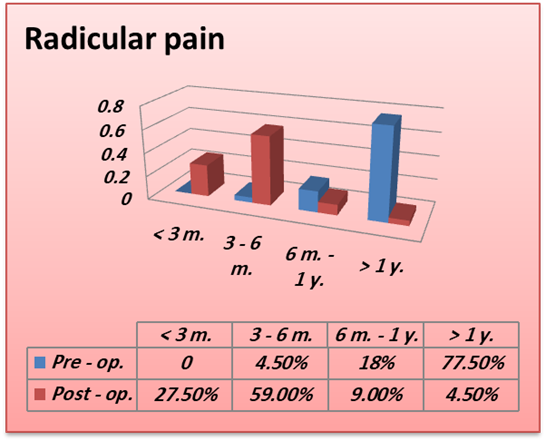

7) Radicular pain: Most of the radicular pain had been subsided in the period of 3–6 months (59%), & just (4.5%) of the patients still had pain for up to 1 year (fig. 7).

Fig. 9. Bar chart shows the duration of radicular pain pre- and post-operatively. However, most of the patients 77.5% had long-standing chronic pain (> 1 year) prior to the operation. After hemilaminectomy 27.5%, of the patients had no more pain and 59 % of them the pain subsided completely within 3–6 months. 4.5% of the patients still had pain that persisted for the entire period of the post-operative observation (1 year)

8) Weakness: Mild weak dorsiflexion was found in 8 patient (36%) pre-operatively, 3 of them (37.5%) unilaterally & 5 bilaterally (62.5%). This weakness was completely improved after the surgery but in different durations (fig. 8).

Fig. 10. Bar chart shows the weakness pre. & post-operatively. Complications

Complications

We didn't encounter any complication. Despite that we need to follow up the patients for up to 5 years to detect if the instability will occur or not.

Discussion

Lumbar spinal stenosis is a pathological condition that is increasingly seen in elderly patients. It originates from typical patho-anatomical changes leading to a narrowing of the spinal canal. The ligamenta flava thicken, the facet joints hypertrophy, and a progressive disc degeneration results in a narrowing of the neural pathways [11, p. 393-397]. Patients often present with a history of numbness, weakness, and radicular pain. Neural claudication is one of the key features, and it may be difficult to differentiate it from vascular impairment.

Although different surgical methods of decompression are available, the general aim is to achieve a sufficient decompression while maintaining segmental stability. Patients with symptomatic stenosis should undergo multimodal conservative treatment for up to 3 months and then be considered for surgery [12, p. 103-105; 13, p. 50-55].

Radiological Evaluation: Radiographs should include plain as well as functional views to exclude spondylolisthesis and developmental disorders. Some of the characteristics of spinal stenosis, such as short pedicles, a short inter-pedicular distance, and degenerative changes in the 3-joint complex, will also be present on plain radiographs [14, p. 31-53].

To delineate the level of the stenosis, several techniques were available, including MRI, & CT scanning. The advantages of these techniques are demonstrating the levels of the stenosis, the possible compressive elements on neural structures, and the pathological changes of osteo-ligamentous and neural components of the lumbar spine [15, p. 129-131]. This modality seems to offer the greatest potential for the future evaluation of lumbar spinal stenosis [14, p. 31-53].

Unilateral Partial Hemilaminectomy: Less invasive procedures, such as unilateral partial hemilaminectomies with transmedian removal of the compressive elements, are being used more frequently for the decompression of lumbar spinal stenosis in elderly patients [16, p. 166-173]. This procedure is of a shorter duration. Compared with laminectomy, a unilateral partial hemilaminectomy results in less injury to paraspinal structures and provides a sufficient decompression. In their series, Kalbarczyk and colleagues [17, p. 637-641] reported that a high percentage of results after interlaminar decompression (32%) were the similar to that after a standard laminectomy. Although interlaminar decompression uses a more limited tissue- and stability-preserving approach, it still seemed to be sufficient for decompression.

Spetzger et al. [18, p. 392-396] demonstrated that less invasive and more limited interlaminar decompression resulted in an increase in interfacet diameter measured on postoperative neuro-radiological images, as well as in gross pathological specimens. This surgical approach preserved the neural arch and protected the dura from epidural scarring. The main advantages of this limited approach are a reduction of the surgical trauma and the avoidance of surgically induced instability. The facet joints are spared, because only the hypertrophic and compressive medial parts are resected. Midline structures (interspinous ligaments and thoracolumbar fascia) are completely preserved. The contralateral supporting lumbar musculature with its physiological attachment to the spinous process is not disrupted, and the integrity is left intact [18, p. 392-396].

Neurogenic claudication: In our study, 18 of the 22 patients with neurogenic claudication (81.8%) demonstrated a marked improvement of the walking distances after the decompression. Spetzger U and colleagues found in their study that 25 of 27 patients with neurogenic claudication (93%) demonstrated a marked improvement of the walking distance postoperatively. Their mean follow-up time was 18 months [18, p. 392-396]. Charles G. diPierro and colleagues found in their study that of the patients with neurogenic claudication (69%), reported complete relief at follow-up review. The minimum and mean postoperative follow-up times were 2 and 2 1/2 years, respectively [19].

Radicular pain:- In our study, radicular pain had been subsided within the first 3 months postoperatively in (27.5%) of the patients, while in about (59%) of the patients, the pain had been relieved in the period of 3–6 months post-operatively, & just (4.5%) of the patients still had pain for up to 1 year. Charles G. diPierro and colleagues found that in their study of the patients with radicular pain (41%), had complete relief and (23%) had mild residual pain that was rated 3 or less on a pain – functionality scale of 0 to 10. Papavero L [20], and colleagues found in their study that at the first week after surgery, pain decreased in (85.9%) of patients, & at the first year after the surgery, the pain remained decreased in (83.9%) of the patients.

Conclusions

Hemilaminectomy is as effective as total laminectomy in decompression of single level spinal stenosis.

Hemilaminectomy carries a less risk of destabilization of spine in single level spinal stenosis.

It is effective procedure for bilateral decompression of spinal stenosis.

.png&w=384&q=75)

.png&w=640&q=75)